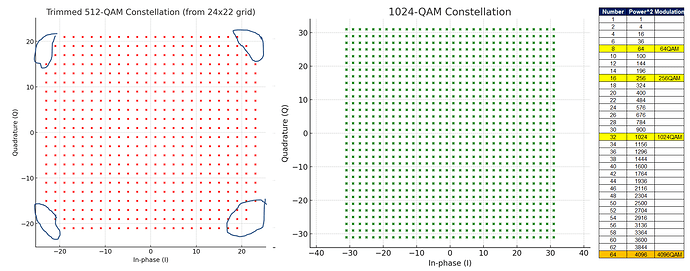

Answer : If we check constellation diagram below 512QAM and 1024QAM ,you find 512-QAM always needs either an uneven grid (like 24×22, 32×16, etc.) or clipped corners to make 512 points — which leads to irregular energy distribution, non-uniform spacing, and hardware inefficiency. That’s why vendors skipped it and went directly to 1024-QAM (32×32).

Thanks @Fathy_Farouk, good point.

In practice, the industry skipped 512QAM because the gain just didn’t justify the added complexity. It only offers about a 12.5% increase in throughput over 256QAM, but it requires almost the same SNR as 1024QAM.

So from both a technical and commercial standpoint, it didn’t make sense to invest in standardizing and deploying it. On the other hand, 1024QAM gives a solid 25% gain and fits much better with network improvements like beamforming and massive MIMO in 5G.

Also, higher-order modulations are much more sensitive to noise and interference. By the time the network conditions are good enough to support 512QAM, you might as well just go straight to 1024QAM. It really came down to a cost-benefit decision — in terms of chipset design, network tuning, and overall efficiency.

This is the same reason why we don’t have 8 QAM, 32 QAM, 128 QAM.

We didn’t skip anything particularly to 512 QAM.

We are using 4^x points for all 4 quadrants, where

X = 1 => 4 points, QPSK

X = 2 => 16 points, 16 QAM

X = 3 => 64 points, 64 QAM

X = 4 => 256 points, 256 QAM

X = 5 => 1024 points, 1024 QAM

@Sakshama Ghoslya

Why do we need 4^x points ?

What happens, if there are less than 4^x points in the signal constellation ?